|

|||||||||||||||||

| Location, Location, Location. | |||||||||||||||||

|

Much of the success of power spinning relies on the humidity of the air, which, as locals will tell you with a hint of irony, makes the North West of England a very suitable location. Most early cotton mills were run by water power and manufacturers preferred to build on the banks of soft water streams. This provided water not only to power the mill wheel, but for processing the raw cotton fibre. When water power eventually gave way to steam, the mills were close to the Lancashire coal fields and a cheap supply of fuel. Additionally, as the industry grew, increasing supplies of raw cotton were imported from America and Stockport was ideally situated to obtain supplies from Liverpool, which was rivaling Bristol to become the chief port for trans-Atlantic trade.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Technology, Economics and a smattering of Politics | |||||||||||||||||

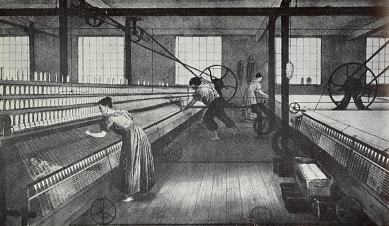

| Inventions such as Hargreaves’ Spinning Jenny and Samuel

Crompton’s “Mule” meant that mechanization of the spinning process

occurred early, and revolutionized the industry in the late 18th

century. Weaving was much slower to develop and it was not made

technically or economically successful until the early 19th

century. Textile workers had thrived in the late 18th century

and handloom weavers especially enjoyed good wages and a relatively high

status, but by 1815 it was reckoned that the power loom allowed one weaver

to equal the output that 200 hand loom weavers

had been able to achieve in the 1760's. The French wars from 1795 onwards reduced foreign trade, and then an embargo was placed on American cotton imports during the war of 1812-14. After the war, the Corn Laws exacerbated problems for workers: Britain could not import cheap foreign grain, factory sales at home and overseas were low, and wages were still falling well behind the rate of inflation. Many people, including men returning from the wars in Europe sought to find work in the textile trades, and there was a glut of labour. This, combined with the other economic problems that the cotton industry was facing, meant that real wages fell by a half. Thousands of workers became unemployed; stretching a system of poor law relief that was antiquated and inadequate. There was widespread discontent about the hardships imposed by the Corn Laws and the potential threat of the new technology, which precipitated an outbreak of machine breaking riots by groups such as the “Luddites”. In the North-West of England the discontent peaked in 1819 when a huge crowd of 50,000 people who had gathered in Manchester to protest for reform and representation in Parliament were broken up by the local Yeomanry; an event which became known infamously as The Peterloo Massacre. Eleven people were killed, and 400 injured. Reform was slow in coming, despite the efforts of people on both sides of the law:- from the machine breakers and from politicians such as Stockport's Anti-corn law MP Samuel Cobden - but the power looms were there to stay. Spinning mules were made "self acting" (fully automated) by 1830 and by 1850, both spinning and weaving processes were almost entirely mechanized. No significant changes were introduced in the Lancashire or Cheshire mills for the rest of the century.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Social Background | |||||||||||||||||

|

A survey by the Factory Commissioners in 1833 gives some indication of the average weekly wages for Lancashire cotton workers:

The familiar phrase “dark satanic mills” used by Blake conjures up a vivid image of textile mills in the 19th century; but surprisingly, the industry was one of the first to become regulated, with restrictions on hours, and conditions, especially for women and children. The limitations seem rather extreme to our modern eyes, but these should be judged by the realities and mores of the times- not our own.

By the time Job Hooley was born in 1851, children between the ages of eight and thirteen were restricted to working 6.5 hours a day, or 10 hours on alternate days in textile factories. Part time school attendance was provided for in the factory act of 1844. Nationally, the Education Act of 1870 permitted attendance for all 5-13 year olds, though school attendance was not made compulsory for all children under 10 until 1880.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Job Hooley was born in the middle of a great period of change, when technology had transformed the lives of textile workers from home based cottage industries using little or no machinery to a highly mechanised factory system which had enormous impact on social demographics. There had also been a long period of political unrest, but social reforms had yet to catch up with the needs of this new urbanised society. Political representation was practically non-existent for those who owned no property, and even after the reform of the Poor Laws in the 1830's the only form of social "umbrella" was the infamous Workhouse. People simply had to deal with the realities of life, adapting as best they could to circumstances beyond their control, whether caused by world wide economics, politicians in London or developments in technology. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||